Children’s custody: a decade of missed opportunities and decline

In this blog, Angus Jones, HMI Prisons Team Leader for Children and Young People, talks about the sustained failure to improve outcomes for the small number of children in custody.

In 2014, the year I joined HM Inspectorate of Prisons, there were reasons to be optimistic about children’s custody; the number of children held was falling fast and inspection reports showed a reasonably good picture at most young offender institutions (YOIs).

The Youth Justice Board, then responsible for commissioning institutions that held children, was embarking on a programme of reform known as ‘transforming youth custody’ to ‘improve education and resettlement outcomes for young people in custody, contribute to reducing reoffending and reduce the costs of custody’[1]. A key proposal was to establish a network of ‘Secure Colleges’ to cater for the vast majority of children in custody. The aspiration within transforming youth custody to provide every child with 30 hours a week of education was never achieved and the Secure Colleges were not built.

In 2016, the Taylor review recommended that the government replace YOIs with ‘Secure Schools’ to make sure that ‘education is truly placed at the heart of youth custody’. Nearly eight years later, there is one much delayed Secure School on an existing site in Kent and about 70% of children in custody continue to be held in YOIs.

The very small numbers of children now held in custody should be a success story, but those children who do continue to be imprisoned are also among the most troubled and difficult to manage; most of whom have been sentenced or are awaiting trial for violent offences, and our inspection reports continue to highlight a very high proportion with experience of being in care. The inability of national leaders to reform the youth justice system as the population has fallen has resulted in a youth custodial estate which has been arrived at by adaptation of an existing unsatisfactory estate rather than by design. Having a small number of youth custodial establishments also means that most children are now accommodated further from home, increasing journey times to and from court, making it harder for them to see friends and family and undermining efforts at resettlement.

This failure has been costly primarily for the children who have continued to be held in YOIs which cannot meet their needs and the communities that have to endure high reoffending rates. It is also increasingly costly for taxpayers; in 2013/14 the Youth Justice Board spent £183 million on an average of 1,318[2] children in custody about £138,506 per child[3], by 2022/23 the Youth Custody Service spent £197 million[4] for an average of 504 children[5] or £390,415 per child. Even accounting for inflation this more than doubling of expenditure has failed to prevent declining outcomes [6].

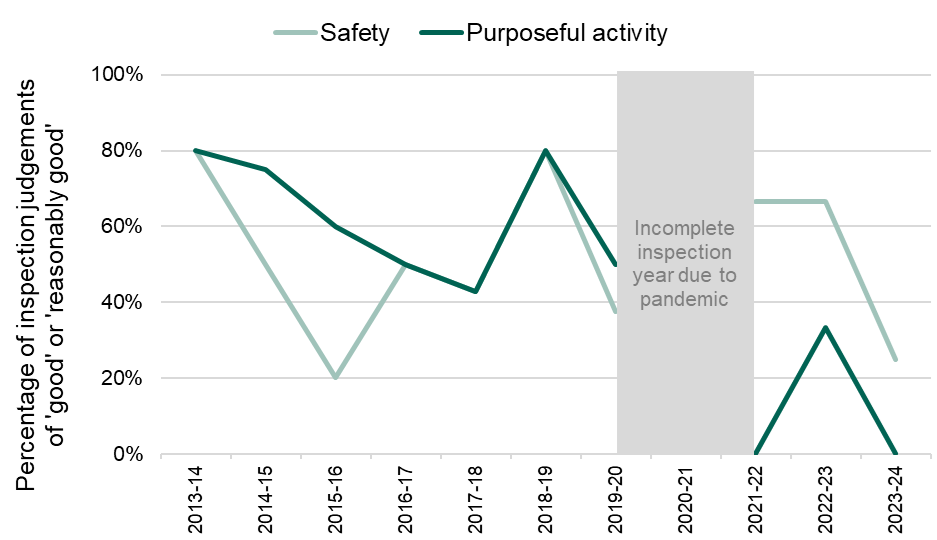

Instead of this investment leading to improvements, the opposite has happened. In 2023-24, YOIs were less safe than ten years before and none of them provided children with a good standard of education[7].

Figure 1: Declining outcomes for purposeful activity in children’s establishments with safety outcomes more volatile year-on-year

Healthy prison judgements of ‘good’ and ‘reasonably good’ in HMI Prisons inspections of YOIs in England and Wales since 2013-14 annual report year

Source: HMI Prisons inspection reports. Note Wetherby and Keppel unit received separate judgements until 2023-24. Not all children’s establishments were inspected in each annual report year.

Our inspection reports in 2023/24 have documented establishments that are unable to manage very high levels of violence and disorder. In most YOIs, leaders resort to keeping children who are in conflict with one another apart, but the levels of conflict are such that this approach prevents children accessing education or offending behaviour programmes and results in most children spending the overwhelming majority of every day locked up alone in their cells. Today, we have published a report on the continuing use of separation, which found that many children continue to be subject to solitary confinement and unable to access the basics of everyday life, including showers and exercise.

Depressingly, despite the effort that has gone into separating different groups of children, violence remains consistently high. In 2022-23, the most recent year with published data available, there were 385 assaults for every 100 children held in youth custody, a rate 14 times higher than in adult prisons in the same period[8].

Self-harm is also extremely high driven by the very small number of girls held in custody. In 2022-23 the rate of self-harm was 9,177 per 100 girls. This was not only much higher than the rate for boys (156 per 100) but also substantially higher than adult women (583 per 100).[9]

These girls are held in a custodial system that is primarily designed to meet the needs of boys.Too often the only tangible response to self-harm is to restrain girls, which while on occasion is necessary, further traumatises already vulnerable girls and results in a high number of assaults on staff.

The inability of national leaders to see proposed reforms through has led to a dysfunctional system of four different types of institutions for just 500 children. This muddled, fragmented approach is failing children and increasing the likelihood that they will go on to become adult offenders. What is needed over the next ten years is action, not further diagnoses. Rather than piecemeal initiatives the Youth Custody Service needs to focus on reducing the number of children held in YOIs by investing in a new estate that can meet their needs.

References

[1] The Youth Justice Board for England and Wales Annual report and Accounts 2013/14 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/656869f25936bb000d316783/15.85_HMPPS_annual_report_2022-23_WEB.pdf

[2] Youth justice annual statistics 2013-2014

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/youth-justice-annual-statistics-2013-to-2014

[3] Calculated using YOI, SCH and STC expenditure and STC and payments made by sponsoring department to STCs and YOIs. Figures from The Youth Justice Board for England and Wales Annual report and Accounts 2013/14.

[4] HMPPS annual report 2022/23 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/656869f25936bb000d316783/15.85_HMPPS_annual_report_2022-23_WEB.pdf

[5] Youth custody data shows an average of 504 children and 18 years olds in custody during 2022/23 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/youth-custody-data

[6] Bank of England Inflation calculator using Consumer Prices Index data shows £182,551,000 in 2014 would be £241,551,000 in 2023. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

[7] HMI Prisons annual report 2023-4

[8] Youth Justice Statistics: 2022 to 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/youth-justice-statistics-2022-to-2023/youth-justice-statistics-2022-to-2023-accessible-version#behaviour-management-in-the-youth-secure-estate compared to Safety in Custody Statistics, England and Wales: Deaths in Prison Custody to June 2023 Assaults and Self-harm to March 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/safety-in-custody-quarterly-update-to-march-2023/safety-in-custody-statistics-england-and-wales-deaths-in-prison-custody-to-june-2023-assaults-and-self-harm-to-march-2023#assaults-12-months-to-march-2023

[9] Youth Justice Statistics: 2022 to 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/youth-justice-statistics-2022-to-2023/youth-justice-statistics-2022-to-2023-accessible-version#behaviour-management-in-the-youth-secure-estate compared to Safety in Custody Statistics, England and Wales: Deaths in Prison Custody to June 2023 Assaults and Self-harm to March 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/safety-in-custody-quarterly-update-to-march-2023/safety-in-custody-statistics-england-and-wales-deaths-in-prison-custody-to-june-2023-assaults-and-self-harm-to-march-2023#assaults-12-months-to-march-2023