- Ofsted is the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills. We inspect services providing education and skills for learners of all ages, including within prisons. HMI Prisons is an independent inspectorate whose duties are primarily set out in section 5A of the Prison Act 1952. In England, Ofsted and HMI Prisons jointly inspect ‘purposeful activity’ in prisons and young offender institutions (YOIs). Both inspectorates expect that prisoners are able to engage in activity that is likely to benefit them. Ofsted inspects the education, skills and work activity within prisons as part of these joint inspections and HMI Prisons inspects time out of cell and the leadership and management of purposeful activity.1 Since February 2020, Ofsted’s inspections have been aligned with the Education Inspection Framework (EIF) contextualised for prisons and YOIs, which has been included in HMI Prison’s Expectations (the independent criteria in which we inspect the treatment and conditions for those detained in prisons and YOIs).2

- Both Ofsted and HMI Prisons suspended their routine inspections on 17 March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Between April and July 2020, HMI Prisons’ conducted a series of Short Scrutiny Visits (SSVs) which focused on a small

number of issues essential to the care and basic rights of those detained. Since late July 2020, SSVs have been replaced by more intensive Scrutiny Visits (SVs), which are short inspections that focus on how establishments are recovering

from the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. - From January 2021, Ofsted plan to carry out interim visits to review prison education alongside HMI Prisons during SVs, and in some cases alone, now that prisons are beginning to return to delivering education, skills and work activities. Until 15 February, all visits will be conducted remotely. Ofsted aim to conduct 25 visits in total, to ensure all prison geographical areas are covered. Visits will be focused on poorer performing prisons and YOIs. These interim visits will not have any grades or progress judgements but will result in findings and recommendations. Each visit will be subject to health and safety considerations.

- Our response draws on Ofsted’s and HMI Prisons’ inspection findings from previous years in prisons holding adult men and women, as well as YOIs. We have particularly focused on evidence from inspections conducted during April 2019 to March 2020. In addition, our response includes evidence from HMI Prisons’ 35 SSVs conducted between April to July 2020, as well as 14 SVs which were conducted between late July to December 2020, which also included a prisoner survey.

Inspection findings before COVID-19

- Before February 2020, Ofsted inspections were aligned with the Common Inspection Framework (2015). Since 2014, Ofsted has provided an overall effectiveness grade for education, skills and work activities. These overall effectiveness gradings provide an insight to the overall state of prison education across prisons in England.

| Total number of prisons inspected | Number of published inspections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | Good | Requires impovement | Inadequate | ||

| 2019/20203 | 32 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 4 |

| 2018/2019 | 45 | 1 | 17 | 20 | 7 |

| 2017/2018 | 41 | 0 | 16 | 20 | 5 |

| 2016/2017 | 41 | 1 | 22 | 12 | 6 |

| 2015/2016 | 42 | 2 | 14 | 20 | 6 |

- Over the last five inspection years, approximately 40 prison and YOI inspections were carried out each year. Only 40% of prisons/YOIs inspected received good or outstanding overall effectiveness grades, meaning 60% were judged to be providing education and skills training which was inadequate or required improvement. Ofsted has reported the same very low level of performance in 3 prisons every year without any perceptible improvement over the last five-year period.

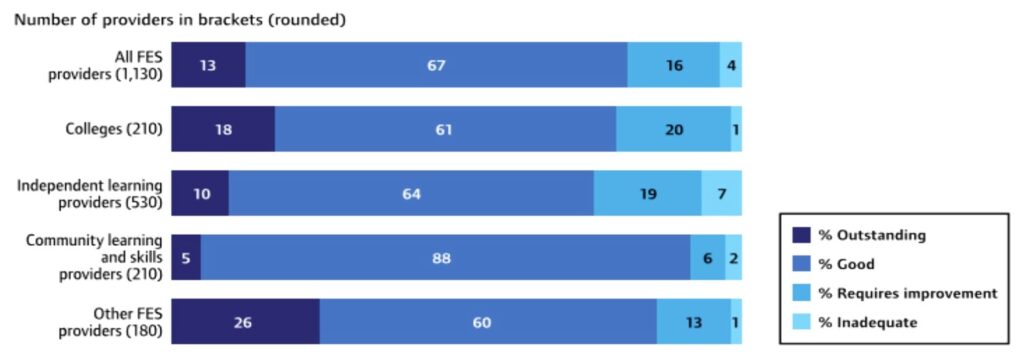

- The 40% of prisons which are good or outstanding for their education and skills activities is strikingly lower than the proportion for other education providers in the further education and skills sector where 80% of further education and skills providers are judged to be good or outstanding overall (see Annex 1). Most prisoners are receiving a standard of education and skills training which is not good enough.

Findings from inspections conducted between 2019-20

- Similar proportions of less than good judgements are to be found for the other key judgements which make up the overall effectiveness grade, as can be seen below from the inspection grade data from inspections of prison education between April 2019 and March 2020.

| Overall effectiveness of education, skills and work | Achievements of prisoners engaged in education, skills and work | Quality of teaching, learning and assessment | Personal development and behaviour | Leadership and management of education, skills and work | |

| Outstanding | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Good | 10 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 10 |

| Requires improvement | 19 | 15 | 20 | 12 | 19 |

| Inadequate | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

- In men’s prisons during the period between April 2019 and March 2020 we published 36 reports, only 39% of the prisons inspected were found to deliver good or better outcomes, which can be seen in the ‘Achievements of prisoners’ column of the table above.

- Ofsted’s overall assessments of education, work and skills in the five women’s prisons that were inspected were good, and outstanding at one open prison. All five women’s prisons had sufficient activity spaces for their population, and these were generally well used. The activities were tailored to benefit both short-term and long-term prisoners. There was good use of distance learning, and two prisons worked in partnership with higher and further education providers to support prisoners’ access to courses and vocational opportunities.

- In both men’s and women’s prisons, the most common weakness is the low achievement rates in English and mathematics by prisoners. Where prisoners do have a reasonable level of English and mathematics, in some prisons they are nevertheless unable to follow higher level courses In addition, many prisoners undertaking vocational courses did not improve their existing English and mathematical skills any further as these subjects were not included and/or delivered sufficiently well in the vocational curriculum. In three prisons, we found that the achievement of vocational qualifications was also low.

- In a high number of cases, many prisoners who undertook essential work in the prison did not have their employment skills recognised.

YOIs

- In the case of the four YOIs inspected annually, half were found to be good for their overall effectiveness and outcomes and the other half were inadequate or requires improvement. In July 2019, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons invoked the Urgent Notification process for HMYOI Feltham A. At Feltham A, leaders and managers did not gather or use data sufficiently to evaluate children’s achievements. For example they did not measure the number of children who had completed specific courses. This is the first and only YOI to receive an Urgent Notification.

- In the two better performing YOIs, children made good gains in their confidence, knowledge and skills often from very low academic starting points. There were no differences in the progress and achievement of different groups of learners, including those with a learning disability or difficulty which accounted for more than half the learners.

- However, we found in only one of the four YOIs that the vast majority of children undertaking an English or Mathematics qualification at levels 1 and 2 demonstrated very good progress and passed at their first attempt. Achievement of these qualifications in the other establishments remained too low. For example, in one YOI, only around a third of children who started a course in English or Mathematics functional skills went on to complete and achieve it.

- Weaknesses in all of the key areas graded contribute to overall effectiveness which is inadequate or requires improvement.

- Leadership and management is a crucial factor in the success of education and skills training in prisons. This necessarily depends on the capacity, capability and commitment of individual governors, managers, teachers and trainers to ensure that prisoners get quality education and training.

- At a higher level this depends on the priority given to education and skills training in individual prisons, but also within the prison service more generally when set against all of the other challenges that governors and staff face in prisons. This needs to be addressed at the highest level in order that prison staff can be enabled to deliver a good quality of education and training throughout the prison service not just in some prisons. In her 2016 report Unlocking potential: a

review of prison education Dame Sally Coates recommended a number of steps that should be taken to ‘put education at the heart of the regime, unlock the potential in prisoners, and reduce reoffending’.4 A great deal remains to be done to realise this. - We believe that secure children’s homes (SCH) are better equipped than secure training centres (STC) to meet the needs of these vulnerable and complex children, despite the recent dip in performance across the SCH sector. For the most part, SCHs provide an environment where children are well cared for and their needs are assessed and met.

- In SCHs, children make good progress in education. For example, Barton Moss SCH has been judged by Ofsted as ‘outstanding’ for the last nine years. It provides high quality provision, care and education for children who are remanded to custody or serving a sentence and where children make positive progress and have positive experiences.

- SCHs have higher staff to child ratios and are smaller, providing a homely, nurturing and caring environment.

- The two STCs inspected between April 2019 and March 2020 had not made the changes necessary to improve their effectiveness, including their approaches to managing children’s behaviour. Education mangers and teaching staff had worked well during the ongoing preparation for the closure of the Medway STC. Inspectors at Oakhill STC found education and learning required improvement. An assurance visit to Oakhill STC in January 2020 found attendance at outreach education sessions was high earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic and most children completed their work packs. In September, lessons had been resumed for five hours each day, and children’s attendance and engagement had been consistently good.

- The concerns that the joint inspectorates found at two recent assurance visits to Rainsbrook STC in October and December 2020 were so serious that the Urgent Notification process was invoked. During the joint assurance visit in December, inspectors found that leaders and managers had made limited progress. Amongst other concerns, children had been locked in their bedrooms for substantial periods of time. The regime stated that children should complete three hours education each day in their rooms. Education work packs were issued, and children used an electronic tablet to upload their work, but records were poor and there was no evidence that children’s education entitlement was being met. They received little encouragement to get up in the mornings and there were

very few determined efforts by staff to engage meaningfully with children.

COVID-19 findings

- In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, HMI Prisons’ inspectors found no classroom-based education in any of the adult prisons that were visited during April to July 2020. Local education providers supplied in-cell study packs but while this initial response to regime restrictions was welcomed, most study packs were not targeted to prisoners’ specific needs. Arrangements for providing feedback on prisoners’ work were weak, except in a private prison where on-site teachers supported prisoners’ in-cell learning. In addition to in-cell study packs, prison staff had provided more in-cell activities than usual to help prisoners alleviate boredom. Examples included in-cell exercise routines (sometimes delivered via in-cell televisions), resistance bands, playing cards, puzzles, craft materials, extra television channels, weekly in-cell film screenings, games consoles and donated DVDs.

- During the SVs conducted between late July to December 2020, HMI Prisons’ inspectors found that generic in-cell education packs had garnered little interest among prisoners. In our survey, 60% of prisoners who responded reported that they had received an in-cell activity pack, but less than half said that they found them helpful. Managers in some prisons had taken far too long to introduce individualised education packs, few prisoners had completed them and many packs did not reach teachers for marking.

- Some prisons that inspectors visited had introduced more targeted in-cell education, such as individualised packs which provided some ongoing support for learners. For example, at one training prison HMI Prisons visited in November 2020, in-cell learning packs which covered 39 topics were available and more than 600 courses had been completed by almost 500 prisoners. At another training prison, inspectors found that in-cell packs had enabled 10 prisoners to complete and be awarded qualifications in English at levels 1, 2 and E3. Both inspectorates will have a better understanding of the quality of in-cell learning packs when Ofsted begin to join HMI Prisons on scrutiny visits in February 2021.

- Most education providers initially left establishments due to COVID-19 and did not return until the summer. Once education staff returned to prisons, HMI Prisons’ inspectors found outreach workers engaging with prisoners and some very limited face-to-face teaching support on prison wings. Despite adequate facilities to accommodate socially distanced classroom activity, only one prison we visited had been approved centrally by HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) to re-open classrooms, and many prisoners remained in their cells, instead of progressing their education. Some prisons have continued to run education induction sessions and conduct readiness assessments for the resumption of classes. Distance learning at tertiary level has continued to be supported by some tutors, but many learners undertaking Open University courses and other distance learning have experienced disruption and delay due to COVID-19 regime restrictions.

- Education classes were also suspended at prisons holding women, although workbooks were being distributed. However, at one prison education staff had remained on site and continued initial assessments for English and mathematics. Some limited one-to-one teaching support was given to prisoners at their cell doors and prisoners still worked towards qualifications. Prisoners at one establishment had been able to continue with their distance learning throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, but this had been restricted to in-cell study. At this prison, changes were made just before HMI Prisons’ SSV took place, allowing a small number of prisoners engaged in distance learning to access the computer resources needed. All prisons holding women which HMI Prisons inspected provided prisoners with a wide range of in-cell activities and crafts.

- Prisoners have received a limited regime throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. During the SVs conducted between late July to December 2020, prisoners who responded to our survey reported that their time out of cell, including time spent at education and work, was severely limited. Almost two-fifths of prisoners who responded said that they were out of their cell for less than one hour a day and less than a quarter of prisoners reported that they were unlocked for more than two hours a day. For most prisoners, the short time they were unlocked was to be used for exercise in the open air, to make phone calls, shower and to complete other domestic tasks. For those prisoners isolating or shielding due to COVID-19, the daily regime was often even more restricted. The number of prisoners out of their cells in order to continue their employment varied across establishments. During this period, HMI Prisons’ inspectors found between 10% and 44% of prisoners remained in essential work, such as the kitchen, wing cleaning and serving of meals, and in some ‘essential workshops’, including textiles, recycling and food pack assembly.

- HMI Prisons’ inspectors found children also received a limited regime. While children had reasonably good time out of cell on weekdays at two YOIs, elsewhere they did not have enough time outside their cell to access everyday basics, including association, showers and telephone calls. At Feltham A, children were unlocked on average for only 4.2 hours on a weekday and much less at weekends.

- At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, all face-to-face education was suspended for children and young people in public sector YOIs for 16 weeks following a HMPPS’ directive. HMI Prisons’ inspectors found that children in the four public sector YOIs that were visited during our SSV programme had been locked up for more than 22 hours every day since the restrictions were announced in late March. In the case of two YOIs, visited in early July, this meant children had been locked up for 15 weeks. For part of this period, some children only had 40 minutes out of cell each day. The main cause of this reduced time out of cell was the cancellation of all face-to-face education by HMPPS, which was enforced even when governors believed they had made adjustments in their establishments to allow education to take place safely. Instead, children were offered in-cell education packs. Take-up of these was high in some sites and arrangements for marking and feedback were good. In contrast, children at a private sector YOI received at least three hours of purposeful time out of cell a day, including face-to-face education, when HMI Prisons’ inspectors visited in late April. After a week of running a more limited regime, managers planned, risk-assessed and started delivering two hours of face-to-face education activity every weekday.

- The latest 2019-20 Ofsted annual report stated that “prisoners with additional learning needs receive insufficient support and the range of education, skills and work activities that vulnerable prisoners can access is poor.” lt should be noted that non-English speaking prisoners are included in this group as they have language and communication needs.

- In YOIs, the support for children with additional needs in three of the YOIs was of variable quality and effectiveness. Overall, education staff recorded and responded to children’s additional needs effectively. Additional support was put in place for children with special educational need or education and health care plans but this was not always timely. In the better cases, learning support was effective and well-integrated into lessons, for example enabling children who experienced language difficulties to contribute to activities well.

- In the inadequate YOI, most teachers lacked enough knowledge of the learning barriers that children had and how to support them. As a result, children’s needs were not being appropriately met. A high number of children had specific educational needs, but teachers did not use this information adequately to inform their planning of learning.

- Inspectors have found that prisoners’ employment prospects are improved when prisons and YOIs have stable and effective partnerships with local, regional and national employers. For example, Ofsted found in one prison that: “[L]eaders and managers in this prison were offering an education, skills and work curriculum that met the employment needs of the prisoners very well. Prisoners accessed education and training outside the prison that complemented the curriculum well and enhanced their employability prospects. The excellent links established with employers benefited prisoners, many of whom gained employment on release.”5

- However, during 2018-19, Ofsted also found that: “[I]n a significant number of our inspections, we identified that offenders received insufficient support towards gaining employment on release. In these cases, offenders did not access a curriculum that enabled them to achieve a vocational accredited qualification or to even have their newly acquired knowledge and skills recognised.”

- In too many prisons there is not sufficiently good relations with employers to help ensure that prisoners stand a good chance of obtaining employment on release. Ofsted would suggest that this can be improved by prisons and YOIs doing the following:

- building more training partnerships with local or national employers that train prisoners while in prison and support them to secure a job before they are released. Over the past few years we have seen a few successful initiatives, such as the Halfords academy at a prison holding women;

- working with local and regional employers to establish current and future employment needs and opportunities and adapt education and skills training to help the prisoner obtain employment in sectors and with particular employers where jobs are known to be available (this applies to training and local prisons in particular);

- working with local further education colleges and training providers to improve engagement with employers and understand what works for them;

- drawing upon the skills training expertise of local colleges and providers where possible;

- working with the Local Enterprise Partnerships and local Skills Advisory Panels to understand local and regional skills needs and the local labour market and, furthermore, the likely skills needs in the area in the near future. This is an area where more cross-government collaboration would aid improvement; and

- making better and greater use of release on temporary licence (ROTL). Only a small proportion of prisoners access ROTL despite their entitlement to do so.

- The rates of prisoners’ participation in education remained poor last year (13 out of 36 prisons were found to have poor attendance and punctuality to education, skills and work). This weakness has featured in our inspection reports for a number of consecutive years.

- There are several factors influencing poor attendance. These range from prisons not having enough activity spaces to fully occupy prisoners during the working day; poor processes to allocate prisoners to the available spaces, not taking into consideration priority of need, time left in prison or sentence plans objectives; and prisoners not being encouraged to attend. For example, during HMI Prisons’ inspections from April 2019 to March 2020, only 44% of prisoners who responded to our survey in local prisons said that staff encouraged them to attend education, training or work. In addition, we have found that in many cases, there are not enough prison staff to bring prisoners to education. Other activities in the prison often take priority (legal visits, medication or attending the gym) over attending as much education as planned. At some prisons, inspectors have found a disparity in pay rates between education and other activities, such as the prisoner earnings in commercial workshops, has also acted as a disincentive to attend education sessions in some prisons.

- During HMI Prisons’ inspections from April 2019 to March 2020, inspectors found most prisoners still spent too much time locked in their cells. HMI Prisons’ expects prisoners to be unlocked for 10 hours a day but on average only 13% of prisoners who responded to our survey reported having received this. In local prisons, inspectors regularly found around a third of prisoners locked up during the working day. Time out of cell was generally better in training prisons, but even here fewer than a quarter of prisoners said they received 10 hours a day out of cell.

- Apprenticeships have the potential to be an effective means to ensure prisoners have the skills that employers need on release and the employment opportunities to help make that release a success. However, there are significant but not insuperable barriers.

- The need for regular day release to work on an employer’s premises is challenging, but can be successfully arranged through ROTL. We understand that ROTL had been suspended throughout the lockdown. Currently, each individual prison will be at different stages where they might allow some ROTL. This will be very much a case by case scenario.

- The specific industry standard skills training may be supplied in-house but may also be provided from outside by effective training providers and colleges. Better use can be made of good quality providers of apprenticeships training outside of the prison service.

- Crucial to the success of an apprenticeship programme in a secure setting is employer engagement and buy-in.

- Lack of resources can be a contributory factor to poor education and training provision in prisons. One essential factor is the quality and supply of teachers and whose teaching/ training experience and skills are essential to ensure effective delivery of impactful education and training. However, as can be seen from the grade data above relating to the ‘teaching, learning and assessment’ key judgements, in rather too many prisons, the teaching and learning skills are not sufficient and this shows on poor planning of learning, for example. Furthermore, prison instructors seldom have been developed to support learning in the work activities that prisoners’ access. The ability of the prison service to attract and develop good quality teachers and trainers is crucial to the success of prison education and this needs to be strengthened. It is one more aspect where prison education lacks sufficient priority within prisons to ensure that a good quality of education is being delivered.

- There are particular limitations regarding online and remote learning which hamper the potential for prisoners to learn better. During the COVID-19 pandemic, very little online learning has been able to happen and a big opportunity to learn and receive some tuition in-cell has been lost. HMI Prisons’ inspectors found very limited use of technology to support learning during SVs, apart from at two training prisons. These prisons had used remote iPads to support learning under supervision and had piloted secure education laptops.

- This is not a new limitation. Ofsted has previously reported that in some cases “offenders did not access a curriculum that enabled them to achieve a vocational accredited qualification or to even have their newly acquired knowledge and skills recognised. In addition, they had generally poor access to the designated e-learning platform (virtual campus) to search for job vacancies or to undertake learning.” [Ofsted annual report 2018-19].

The curriculum and quality of education

- Ofsted makes clear the importance of curriculum in ensuring a good quality of education in its education inspection framework. The curriculum needs to be designed in a way that ensures that it is well-structured and sequenced, so learners acquire the knowledge and skills they need so they can progress to their planned next steps, whether these are employment, further study or greater independence. This teaching and learning needs to build on past learning and ensure that what is being learned is secured in to the long term memory (and not just learned temporarily to pass a test or qualification). For a prison education curriculum to be effective it needs to be fitted to the learning and skills needs of its individual prisoners and also take account of the skills needs of employers. The curriculum needs to be regularly reviewed as the prison population and its education and skills needs change.

- A few of the prisons inspected during 2019-20 had improved their curriculum since their last inspection. One prison had used prisoners’ views to inform the curriculum change and other establishments had focused on prioritising the development of employment skills. However, in a similar number of prisons Ofsted also found that the provision of education, skills and work activities did not meet prisoners’ needs; including those of vulnerable prisoners (i.e. those that

are separated from mainstream prisoners for their own safety, well-being or due to their own vulnerabilities). Too frequently vulnerable prisoners are therefore accessing a curriculum which doesn’t take sufficient account of their needs and

does not allow them to make the progress they might be capable of and which they might otherwise have made in the wider community.

- Prisons should act upon recommendations in inspection reports and HMPPS should continue to monitor this. It is very common to find that prisons have not addressed the recommendations from the last inspection report to a sufficient degree or, in some cases, at all. Prison governors also need to be given the means, capacity and capability and discretion to be able to deliver these recommendations.

- Both inspectorates have continued to find that purposeful activity outcomes for prisoners have remained poor, and few prisons have showed signs of improvement. The quality of teaching is too often not good enough, attendance is varied and prisoners do not make the progress that they should. This means many do not acquire the skills they need to gain employment, training or education that will help them to resettle successfully back into the community.

- In Ofsted’s view, education and skills is not given sufficient priority amongst all of the challenges facing prisons managers and staff and so very regularly insufficient progress is made towards improving the quality and standards of education and skills training provided. Until that priority is re-set at the highest level, it seems likely that the same underachievement will be perpetuated as before. Ofsted believes it might now be appropriate to consider strengthening the tools which could be used to require HMPPS to act more promptly and improve the overall effectiveness of education, skills and work in prisons where Ofsted judges the provision to be less than good.

Annex 1: Overall effectiveness of further education and skills providers as at 31 August 2020

- HMI Prisons’ Expectations, which includes Ofsted’s EIF are available at Expectations – HM Inspectorate of Prisons (justiceinspectorates.gov.uk) ↩︎

- Prisons are inspected against the same framework as other education provision, since prisoners should receive the same standards of education that are expected in the wider community.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/inspecting-education-skills-and-work-activities-in-prisons-and-young-offender-institutions-eif ↩︎ - Includes four inspections carried out on or after 1 February 2020 under the education inspection framework which replaced the common inspection framework ↩︎

- Unlocking potential: a review of education in prison – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) ↩︎

- Quotations in paragraph 35 and 36 have been taken from Ofsted’s Annual Report 2018-19 ↩︎